Introduction to OBI data modelling

One of OBI’s missions, to model the logical structure of experimental assays, requires a close study of entity attributes, processes and their input/output participants, and data collection specifications. Some stakeholders are involved only in process modelling in order to document study design and/or protocol details as metadata; others are turning to OBI ontology to provide standardization of data collection and exchange; software developers will require knowledge in both these areas in order to provide the next generation of integration tools. We aim to provide analysis approaches and diagrams to satisfy these needs.

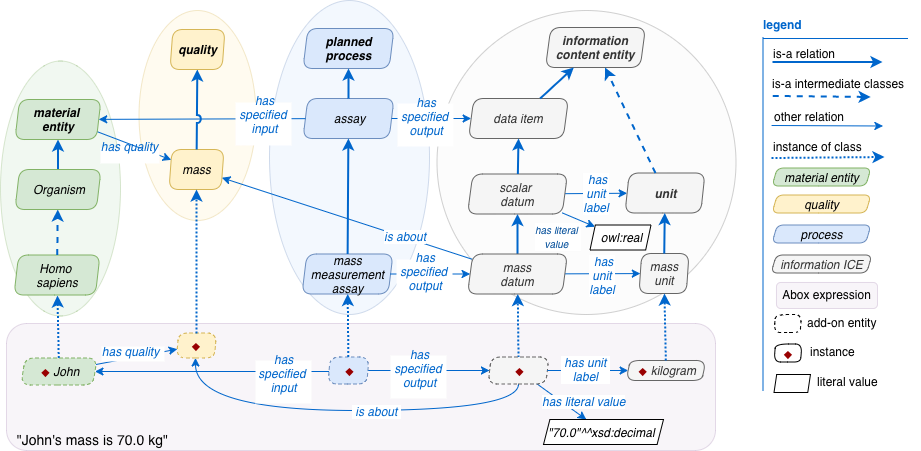

Aligning with BFO, OBI divides references about study design and assay structure into roughly four domains - material entities, their observable qualities, planned processes, and information artifacts, which all show up in process and data modelling.

The following documentation sections will focus on various parts needed to detail processes and their input and output data. The diagram below shows how OBI expresses the statement “John’s mass is 70kg” using object and data properties, and the related material entity, process, datum, quality and value specification ontology components hovering in the background. It shows the big picture - by tracing classes further up the inheritance hierarchy, we can see the impact on instance data. Details on each of these sections follow.

Material entities and their properties/qualities

Under material entity we find OBI’s organism - the usual focus of biomedical investigations. Organism related terms - whether in OBI or in other ontologies that cover taxonomic, anatomic, developmental, pathological, environmental etc. aspects - will likely occur in study design objectives, protocols and experimental observations.

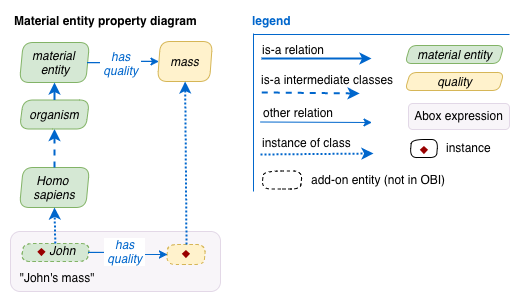

Material entity property diagrams focus on material entities and selected object properties (that link them to qualities) and class-subclass relations, which together illustrate OBI core “terminological component” (Tbox) contents. In the example below, a material entity has quality some mass. (This axiom is not currently in OBI but is included to show the potential for relation inheritance).

Formally, has quality is a generic object property existing between a BFO independent continuent entity (the bearer) and a quality, which is a dependent continuent (i.e. something that depends on the existence of its continuent). Homo sapiens is shown as a descendent of organism, a subclass of material entity, so in this case the descendants also inherit a mass quality that can be referenced. (A dashed arrow between entities indicates that several intermediate classes have been omitted).

An optional rose-tinted box may be provided to illustrate how to compose instances of classes and relations - this is “assertion component” (Abox) content. Abox content can form the bulk of a triple-store graph database, with the reasoning axioms of related ontologies added separately when validation of data structures and models is desired. In this example it is stated that “John” is an instance of Homo sapiens, and bears an instance of mass (or mass quality) that can then be referenced by other expressions. The diagram surrounds the entities of this expression by dashed perimiters to indicate that they are not provided by OBI, but rather are “add-on” entities in another application ontology.

The definition of a quality

Some qualities are easily identified, while other phenomena may not be so easily recognized as qualities. A BFO quality is a directly measurable feature (or attribute) of an entity at any time during the course of its existence. This includes most phenomena measured with the International System of Units (SI) base units, including length, mass and temperature, but does not include measurables that are more a function of time, such as velocity or acceleration, or of context, like location. Color is allowed as a quality insofar as it can be nearly instantaniously measured (although technically a frequency measurement, a function of time).

Ontologies often draw from PATO’s roster of quality subclasses, which (except for PATO process quality branch, see issue 284) can work as BFO quality subclasses too.

A calculation that takes in more than one quality measurement datum for input will not be directly about the related qualities per se. One may have to define the phenomena the calculation describes as an information content entity (ICE), for example, OBI would consider the body mass index, an estimate of body fat ratio, to be an ICE datum which therefore an entity can be bearer of; see BMI example.

“Eyeballing” a measurement does not change whether the measurement is about a quality or an ICE. If the measurement can be achieved with only one quality for input, it is about a quality. If it is necessarily a function of more than one quality, it is an ICE. Examples: assessing the color of an iris is primarily a quality measurement; the focus of the measurement (an iris) is secondary contextual information. The weight of an individual is also a quality measurement (regardless of solar context, on earth or moon, etc.). Judging BMI by looking at a person, or subjectively self-assessing via a likert scale question, is still fundamentally about an ICE, not a quality, as the phenomena being measured necessarily has more than one quality involved.

PATO’s age quality is currently listed as-is in OBI although it is about a time-dependent interval, a duration. OBI currently states that an “age measurement datum is quality measurement of some age”. However this axiom will likely be replaced with more of a consensus position that “age measurement datum is about some duration”. The documentation here reflects this.